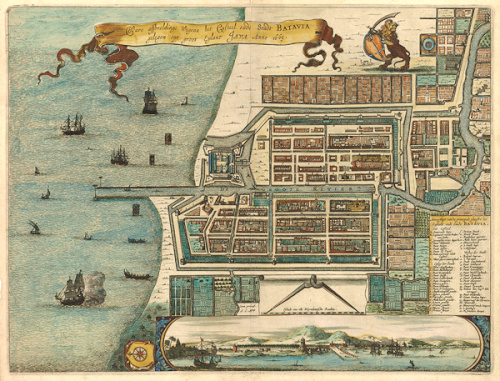

Batavia City and its Environs

After 1619, Dutch sources often still read ‘Jaccatra’. Large collections of archives of Old Batavia are still preserved. Those of the Orphan Chamber (which includes the probate court), Notaries, College of Aldermen (the city court) all date back to the early seventeenth century. Although Batavia became gradually the most important and largest colonial city in Southeast Asia at the end of the seventeenth century (Portuguese Goa and Spanish Manila were two other large colonial cities), research into the city’s history on the basis of primary archival sources has largely been neglected. One of the reasons has been a lack of interest in such an explicitly colonial topic after Indonesian independence in 1945.

Batavia’s city archives offer at first glance information about a number of well-known topics such as the functioning of the city boards, the publication of regulations (‘Plakkaten’) and the history of some of the remaining buildings such as the Town Hall or Stadhuis (1710) and the ‘Portuguese’ church (1696). However, the main challenge for this website is to demonstrate that the daily social life, the ups-and-downs of small entrepreneurship and inter-ethnic and multi-cultural community life can still be reconstructed in great detail. So far, the history of Batavia has invariably been connected to the social lives of the Company elite. Barely has it dealt with the daily reality of the often successful lives of the more than ninety percent of the Asian inhabitants in and around the city.

In particular, the ‘Ommelanden’ or Environs offer a rich field of study. Many present-day names, for example Kuningan, Kalibata(s), Lebak Bulus, Pondok Gedé (Cililitan) already appear in the seventeenth-century books kept by the District Council which supervised the maintenance of infrastructure and registration of landed properties and estates. Kampong life, water management, paddy and sugar cultivation, land ownership, bondage and slave labour, and the intermarriage of people of diverse ethnic backgrounds have emerged as favourite topics in the revision of Batavian history, to say nothing of the origins of the ethnically diverse orang Betawi. The Harta Karun collection has accorded priority to the selection of such documents, which are so revealing about the Asian and Indo (mestizo) citizenry of Batavia, their whereabouts and social life. They have thus helped to give the city back some of its hitherto neglected Asian character.