The Malay and Indonesian World

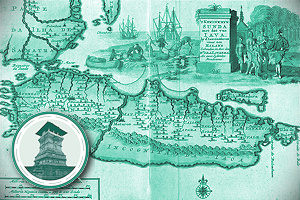

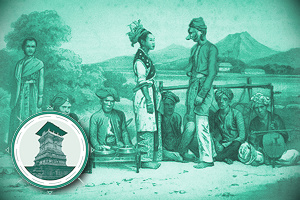

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, kingdoms like Mataram, Aceh, Melaka, Makasar, Banten and Mataram rose and fell. During this period, Malay emerged as the most important language of trade and religion (Islam). the sixteenth-century sultanate of Melaka being the first example of such a Malayanised kingdom in the early modern period.

The eighteenth century, which might be said to begin somewhat earlier at the end of ‘Age of Commerce’ around 1680, is best seen as a separate historical category. Historical developments in this ‘long’ eighteenth century (1680-1800) reveal their own specific characteristics.

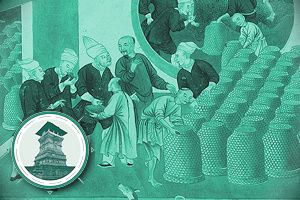

In the early eighteenth century, the production of coffee was first developed in Priangan in West Java thus binding the region ever more closely to the world market. Central Java experienced a number of wars of succession and conflicts over territory and power. In its efforts to control Java’s north coast ports, the Dutch East India Company became ever more deeply embroiled in the various struggles for hegemony in Java. Java was the exception to the rule among the regions of the Malay-Indonesian world. Many other regions such as Johor and Siak, and the dozens of tiny kingdoms in Sulawesi and Bali, as well as the turbulent East Javanese kingdom of Balambangan, remained fairly autonomous throughout the eighteenth century. Although traditional power centres like Ternate and Makassar had fallen into the hands of the VOC, this did not mean that the Dutch controlled the whole of Sulawesi or Maluku.

Older peripheries emerged as new centres. Buginese, Mandarese and Makasarese maritime traders expanded their own networks and settlements along the coasts of Kalimantan, Riau-Johor and Sulawesi generating a lively exchange of goods, ideas and culture across the borderless Melaka Straits, Sunda Shelf and Java Sea. This ‘long’ but complex eighteenth century can be said to have ended on 1 January 1800, when the VOC was wound up and the ‘Dutch’ East Indies (Indonesia) officially passed into the hands of the Netherlands government. After 1800, particularly after the arrival of Governor-General Herman Willem Daendels in January 1808, Dutch – Indonesian relations changed fundamentally.

Looking at ANRI’s early modern collections, one might be tempted to conclude that almost nothing has survived of the inter-insular correspondence between Southeast Asian rulers, traders and men of religion. But this would be wrong. The VOC archive provides information on certain facts and events mentioned in the official histories or court classics such as the Javanese Babad Tanah Jawi (History of the Land of Java) and the Malay hikayat which are first and foremost literary and cultural (genealogical) manuscripts. Unquestionably the archive’s chief limitation is the one-sided contemporaneous European selection of facts and observation of events. These are inevitably affected by the specific interests of the document writers. The challenge is to analyse these documents from a non-European, Indonesian and regional Asian perspective. Fortunately, the Daily Journals of Batavia Castle also include hundreds of letters of Southeast Asian origin. These were delivered by special couriers who operated in an advanced system of information exchange. From the perspective of placing the Malay and Indonesian region at the strategic centre of maritime Southeast Asia, the Harta Karun collection is essential.